Redux

Well, it's been just over a year since I wrote my article on Alejandro Amenábar's film Agora and expressed my misgivings that it would perpetuate some Gibbonian myths about how Hypatia of Alexandria was some kind of martyr for science, how wicked Christians destroyed "the Great Library of Alexandria" in AD 391 and how her murder and the Library's destruction ushered in the Dark Ages. That article certainly attracted some attention and stirred up emotions - so far it's racked up 4,872 page views and attracted 125 comments, many highly hostile.

Of course, when I wrote that article the film had only been screened at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival and so I was simply able to comment on what the director and star said about it in press releases and interviews and on what could be gleaned from trailers and a couple of brief clips. Inevitably, some of those who weren't happy with what I had to say pounced on this and claimed that I couldn't criticise the movie until I'd seen it, even though I made it very clear that I wasn't criticising the film per se and that I would withhold judgement on it as a whole until I'd seen it.

Agora has now been released in both the UK and US and so is attracting rather more attention. Since there is still no sign of when (or if) it will be released here in Australia, I decided to put aside my usual principles and download a copy from the internet so I could finally see it for myself.

The Good, the Bad and the Silly

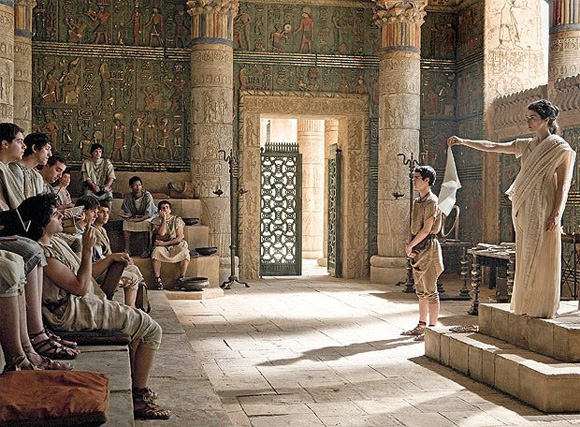

To begin with, there's actually quite a bit to like about this movie. The cinematography is rich and engaging and the sets combine nicely with some judicious use of CGI to give us a vivid reconstruction of late Fourth and early Fifth Century Alexandria. At several points Amenábar pulls the camera out of the action, up into the sky for a bird's eye view of the city and then out into space to look down on the earth as a whole. A few critics have called these the "Google Earth shots", but personally I thought it worked well as a way of noting how petty and insignificant the violent political and religious squabbles at the centre of the story actually were. Amenábar has noted in interviews that he was originally inspired to make the movie by Carl Sagan's 1980s TV series Cosmos and these shots were a nice nod to Sagan's ability put our human concerns into a cosmic perspective (even if, as I detailed in my original article, Sagan also managed to bungle the history of Hypatia rather badly in that series).

I also thought Rachel Weisz and most of the rest of the cast did a very good job with a story and, at times, a script that had the potential to be highly unwieldy. The dialogue was often clunky, as it certainly can be in historical epics like this, but Weisz managed to make scenes where she expounds on the Ptolomaic cosmological model interesting and certainly captured the "self-possession and ease of manner" that Socrates Scholasticus says Hypatia was known for very nicely.

While the sets were impressively detailed, with Roman and Hellenic elements mixed with Egyptian motifs, the same can't be said for the costumes, which tended to be "generic ancient tunics and togas" rather than clothing of the specific period. Even less thought was given to the arms and armour of the Roman troops and the warring factions. It seems no-one can make a "Roman" film without equipping Roman soldiers in generic First Century AD helmets, swords and armour, regardless of what century the film is actually set in. So here the Romans wear what look like left-overs from Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, with brassy-looking pseudo-First Century helmets, short gladius swords and, of course, leather lorica segmentata for armour. It would have been nice for nitpicky obsessives like me to finally see a movie set in the later Roman Period where the soldiers actually look like late Roman troops, but that was probably expecting too much.

The movie does do some playing around with the timeline of events and with the major characters in the story, but most of this can be excused on dramatic grounds. In the first half of the story the Prefect Orestes (Oscar Isaac) is depicted not just as one of Hypatia's students but also as the one who, according to the famous story, publicly declared his love for her and got rebuffed. It's said the historical Hypatia rejected him by presenting him with rags stained with her menstrual blood and said "This is what you're in love with". But because the film never bothers to make her neo-Platonist asceticism clear - exactly what her philosophical views might be is never explored except in the vaguest terms - this incident doesn't really make much cultural sense - she comes across as a modern career academic "married to her job" rather than a disciple of the school of Plotinus.

We know that Synesius (Rupert Evans), who later became Bishop of Cyrene, was one of her students. And in the movie he comes back into the latter part of the story as well and tries to convince Hypatia to placate her enemies by converting to Christianity. Finally, a fictional slave, Davus (Max Minghella), is introduced to provide the third element in an unrequited love triangle with Orestes and Hypatia. All these changes to the historical accounts are fairly tolerable, but where the "history" in the story goes widly off the rails is when Amenábar and fellow screenplay writer Mateo Gil begin their hamfisted sermonising. Then things get silly.

The Library That Never Was

The screenplay includes sufficient elements and details from the actual historical story to indicate that Amenábar and Gil did enough homework to have been able to depict things as they actually happened. But this is a movie with a message and an agenda, so these elements get mixed around, downplayed, countered or simply distorted to suit Amenábar's objectives. More importantly, most of the elements that support the "message" the director is preaching are wholesale fictional inventions.

To begin with, "the Library of Alexandria" forms the focus of the first half of the film. Amenábar depicts this "Library of Alexandria" as forming the core of the Temple of Serapis - in fact, the Temple itself seems almost an adjunct to it - and it is described as containing "all that remains of the wisdom of men". This is historically problematic on several fronts. To begin with, as I detailed in my article last year, there was no "Great Library of Alexandria" as such in the city at this time. The former Great Library had degraded and suffered several major losses of books over the centuries but it had ceased to exist by this stage - the last clear reference to it that we know of dates all the way back to AD 135. We do know from several sources that the colonnades of the Serapeum did contain a collection of books at one time and this was a "daughter library" former Great Library's collection. But Ammianus Marcellinus, who may have visited Alexandria himself when he was in Egypt in the late 360s, refers to the "two priceless libraries" it had once housed in the past tense, indicating they were no longer there by his time. This fits with the descriptions we have in no less than five sources about the sack and destruction of the Serapeum at the hands of the Christians in AD 391: none of which mention any library or books at all. This silence is made more significant by the fact that one of these sources was Eunapius of Sardis, who was not only a vehement anti-Christian but also a philosopher himself. If anyone had an incentive to at least mention this aspect of the destruction it was Eunapius, but he makes no mention of any library or any destruction of books.

So the idea that any "Library of Alexandria" or any library at all was destroyed by the Christian mob in AD 391 is simply without evidential foundation.

Amenábar's screenplay gives some indication that he is aware of at least some of this. The opening titles (in Spanish) do declare explicitly that in Hypatia's time "Alexandria .... possessed ... the (world's) largest known library" (poseia .... la biblioteca mas grande conocida) and a subtitle a few minutes later declares the site of Hypatia's lecture in the opening scene is "the Library of Alexandria" (Biblioteca de Alejandria). But later one of the characters mentions " ... the fire that destroyed the mother library ... ", though this is in a piece of background dialogue while Hypatia is saying something else - less attentive viewers may even miss it completely. Amenábar himself referred in one interview last year to the library in his film as "the second Library of Alexandria", so he clearly understands that the original Great Library no longer existed in AD 391. But he doesn't exactly go out of his way to make this clear to his audience. And he not only includes a library in the Serapeum, despite the evidence even this smaller library no longer existed at this point, but makes it the centre and focus of the whole complex.

Not surprisingly, it is also the focus of the scenes of the storming of the Serapeum by the Christian mob that form the climax of the first half of the film. The accounts of the destruction of the Serapeum make it clear that the mob did not just storm the temple, they tore it to the ground, leaving little more than its foundations. But the movie doesn't depict this at all. Apart from toppling the great statue of Serapis and some other vandalism, the Christians leave the building intact and concentrate almost entirely on dragging the scrolls out of the library and burning them in the temple courtyards. At one point as they swarm through the gate someone can even be heard shouting "Burn the scrolls!", as though this was the whole point of the exercise So, oddly, Amenábar doesn't bother depicting what the mob did do and concentrates instead on something not even hinted at in the source material. He wants to keep the emphasis firmly on the idea of Christians as destroyers of ancient knowledge and reason. One reviewer, accepting this scene as wholly factual, calls it "the movie's most emotionally powerful moment" and says "it really makes you cry". She's blissfully unaware that the whole scene is almost entirely fiction.

Alexandrian Street Politics

The second act of the film concentrates on the disputes within the city that led to the murder of Hypatia. Again, Amenábar and Gil's screenplay indicate that they are aware of some of the complexities of the situation, but their movie's agenda means that it's almost always the Christians who are cast in the worst possible light. Socrates Scholasticus makes it clear that the political struggle for civic dominance between Bishop Cyril and the prefect Orestes had its origin in the Orestes torturing to death a follower of Cyril's, Hierax, who the Jewish community in the city accused of stirring up emnity against them. In response, Cyril threatened the Jews, ordering them to "desist from their molestation of the Christians" and the Jews reacted by setting an ambush for Christians in the Church of Alexander, killing a number of them. Cyril retaliated by setting his mob on the Jews and driving them (or at least some of them) out of the city.

Amenábar depicts some of this tit-for-tat series of threats and violence, but invents a scene where the Taliban-style Parabolani instigate the whole dispute by sneaking into the theatre where the Jews are holding a Sabbath celebration and stoning them. This is found nowhere in the sources but, once again, Amenábar introduces a fictional incident into the story to make the whole conflict with the Jews and the subsequent feud between Cyril and Orestes into the fault of Cyril's faction - a clear distortion of the reported facts.

He also distorts other incidents in the dispute. Again, Socrates Scholasticus reports that Cyril made overtures of a negotiated settlement with the prefect, but "when Orestes refused to listen to friendly advances, Cyril extended toward him the book of gospels, believing that respect for religion would induce him to lay aside his resentment." (Socrates, Ecclesiastical History, VII, 13). Orestes, however, rejected the gesture and refused to be reconciled with the bishop. A garbled version of this incident appears in the movie, but - yet again - Amenábar adds a fictional scene where Cyril implicitly condemns Orestes, not for supporting the Jews, but for being influcenced by Hypatia: something not mentioned in the sources. In this scene, during a church service Cyril reads the passage in 1Timothy 2 where Paul orders women to be modest, to submit to men and to be silent and condemns women teaching men. He then orders Orestes to kneel before the Bible he's just read from in acknowledgement that what Cyril has read is true and Orestes refuses. Amenábar changes the incident to put its focus on Hypatia, despite the fact this scene is almost totally invented.

The movie then moves from this fictional scene to Cyril ordering the Parabolani to respond by attacking Hypatia. So while it does make it clear that this was in retaliation for the torture and death of another of Cyril's followers by Orestes and due to the political struggle between the two rivals - which is factual - by inventing a scene where Cyril condemns Hypatia for being a woman who teaches men Amenábar sets up the idea that this was the also a reason Hypatia was targeted - which is not factual at all. But it serves his ideological purpose of implying that Hypatia's learning was a major issue, not simply the political faction fighting.

None of the factions come out of the movie looking particularly good, but these invented scenes do their best to cast Cyril and his followers as the instigators of the trouble and make them the clear villains in what was, on all sides, a rather grubby power struggle. It's very odd that Cyril and most of his Parabolani fanatics are swarthy types who, despite being native Alexandrians, speak with thick Middle Eastern accents. They also always wear black. The pagans and members of Orestes' faction, on the other hand, all speak with clipped upper-class English accents and tend to wear white. The implications here are less than subtle.

Fictional Science and Supposed Atheism

The final major invention by Amenábar which also suits his agenda is the rather fanciful idea that Hypatia was on the brink of not only proving heliocentrism when she was murdered but at establishing Keplerian elliptical planetary orbits into the bargain. The film makes reference to the fact that Aristarchus of Samos had come up with a heliocentric hypothesis in the 300s BC, and mentions a couple of reasons it was regarded as making "no sense at all" (though doesn't mention the primary one - the stellar parallax problem). But it invents a series of scenes depicting Hypatia pressing on with this idea despite these (then) not inconsiderable objections. The whole purpose of these sequences is to make the murder of Hypatia seem like more of a loss to learning at the hands of ignorant fundamentalists. Hypatia was certainly renowned for her learning, but there is actually no evidence she was any great innovator, let alone that she had any interest at all in Aristarchus' long-rejected hypothesis. In fact, as the daughter of Ptolemy's most famous ancient editor and commentator, the idea that she would reject the Ptolemaic model of cosmology is pretty far fetched. Once again, it's Amenábar's invented elements that work to support his agenda of simplifying the story into one of "ignorance and fanaticism versus scholarship and inquiry".

The movie also heavily implies that Hypatia was entirely non-religious or even an atheist - something else not found in any of the source material. Confronted with the accusation that she is without any religion ("someone who, admittedly, believes in absolutely nothing") Hypatia replies, rather vaguely, "I believe in philosophy". Later Cyril describes her as "a woman who has declared, in public, her ungodliness". In fact, of all the pagan schools of thought, the neo-Platonists were the closest to a monotheistic view of the world, which is why first Jewish and then early Christian theologians took on board so much of their philosophy and integrated it into their ideas. Yet again, Amenábar invents something that has no basis in any of the evidence that suits the sermon his movie is preaching.

Over and over again, elements are added to the story that are not in the source material: the destruction of the library, the stoning of the Jews in the theatre, Cyril condemning Hypatia's teaching because she is a woman, the heliocentric "breakthrough" and Hypatia's supposed irreligiousity. And each of these invented elements serves to emphasise the idea that she was a freethinking innovator who was murdered because her learning threatened fundamentalist bigots. The fact that Amenábar needs to rest this emphasis on things he has made up and mixed into the real story demonstrates how baseless this interpretation is.

Reactions

It may be baseless, but it's receiving a predictably enthusiastic reception by many critics and moviegoers. One IMDB reviewer certainly got the message, writing a glowing review entitled "Atheists of the all the world unite!". Another notes, "Amenábar made a statement before the screening that if the Alexandria library had not been destroyed, we might have landed on Mars already." A third declares "I hope the film is appreciated and understood, and that we learn a little bit from its depiction of history so that we can't allow the destruction of art, history, knowledge, and the respect that allows civilizations to flourish." And these comments are typical. These viewers accepted all the invented pseudo historical additions to the story without question and happily swallowed the sermon they rest on.

Several blog posts and articles have attempted to counter these distortions of history (notably Father Robert Baron, decentfilms.com, Jeffrey Overstreet, and the Catherine of Siena Institute). All these writers are, however, Christians. While several of them have attempted to deflect the charge that they are biased by reference to my article of last year (one poster on artsandfaith.com notes that I am "an atheist, no less!"), I know from my encounters with true believers in The Da Vinci Code that their Christianity will mean these attempts will be generally rejected or ignored - people like to cling to myths that confirm their ideas.

Which means, rather ironically, this film exposes who are the true fundamentalists in this picture.